PJ Harvey, The Hope Six Demolition Project (Island Records, 2016)

PJ Harvey & Seamus Murphy, The Hollow of the Hand (Bloomsbury, 2015)

PJ Harvey, Let England Shake (Island Records, 2011)

PJ Harvey, Let England Shake: 12 Short Films by Seamus Murphy (Island Records, 2011)

by Rebecca Varley–Winter

Here’s the Hope Six Demolition Project and here’s Benning Road, the well-known “pathway of death”. Here’s the I-HOP – the one sit-down restaurant in Ward Seven. Nice. Okay, this is drug town. Just zombies. Lotsa wig shops, lotsa baby-mamas as they call ’em. The Mayor planted trees. See how the trees make it better… So here we are on one more pathway of death and destruction…

(‘Sight-Seeing, South of the River’)

In a recent article for The Washington Post, Paul Schwartzmann describes giving a windshield tour of “Washington’s roughest neighborhoods” to the photographer Seamus Murphy and his collaborator, a mysterious musician and poet who listened quietly from the back seat:

And here was East Capitol Street, where the city had replaced a notoriously violent housing project with mixed-income townhouses, created under a federal program known as Hope VI.

At Alabama Avenue and Naylor Road, I paused in front of the largely vacant Skyland Shopping Center.

“They’re gonna put a Walmart here,” I said.

In my mirror, I could see Polly scribbling in her journal.

“Polly” was PJ Harvey, gathering material for her first published book – a collaboration with Murphy titled The Hollow of the Hand (2015) – and her new album, The Hope Six Demolition Project (2016). Her poem ‘Sight-Seeing, South of the River’ and its corresponding song, ‘The Community of Hope’, clearly take their material from Schwartzmann’s tour:

This “(at least, that’s what I’m told)” becomes something of a wry get-out clause: Harvey’s poems and songs channel voices other than her own, allowing her to hide in the mist of reportage. [1] ‘The Community of Hope’ has nonetheless been accused of poverty tourism: Harvey is, after all, relatively affluent, exploring poor and war-torn regions as a roving reporter-poet. Her perspective in The Hollow of the Hand seems to fluctuate between an idealistic belief in transcending national, religious, economic and racial divisions, and consciousness of her distance within the communities she enters. Throughout The Hope Six Demolition Project, we hear varieties of call-and-response between her lone voice and a bigger chorus: in ‘The Community of Hope’, a gospel choir ecstatically sings “They’re gonna build a Walmart here!” as the song fades. One local charity argued with Harvey’s depiction: “By calling out this picture of poverty in terms of streets and buildings and not the humans who live here, have you not reduced their dignity?”

This would be unfortunate, as it’s fairly clear that the residents of Hope VI are not Harvey’s intended target. She takes aim at the horsemen of inequality, suffering and war, but their causes tend to diffuse under scrutiny, everywhere and nowhere, so the songs grope through limbo, searching for a smoking gun. Harvey has visited America before, in Stories from the City, Stories from the Sea (Island Records, 2000), and there are echoes of ‘Big Exit’ and ‘The Whores Hustle and the Hustlers Whore’ in ‘The Community of Hope’. “I see the children / Dead end lives”, and “this city’s ripped right to the core”, she sang then, on the cusp of 9/11, long before the financial crash of 2008: these aren’t new preoccupations. However, Stories from the City barely approached her current merging of poetry, music and photojournalism: Hope Six continues the trajectory of Let England Shake (Island Records, 2011), which grappled with the reverberations of Britain’s twentieth century wars. Now she travels to Afghanistan, Kosovo and Washington D.C. As she told the Guardian: “Gathering information from secondary sources felt too far removed, […] I wanted to smell the air, feel the soil and meet the people of the countries I was fascinated with”. Laura Snapes divines her intent: “If there’s a unifying thread between the desolate global vignettes of The Hope Six Demolition Project, it’s that Washington has a tendency to leave its business unfinished. […] This is her Let America Shake”.

As Harvey is no longer on home turf, her depictions have met with greater resistance, particularly her portrayal of a native American woman in ‘Medicinals’, sipping “a new painkiller / for the Native people”. It’s the most obvious groan-point of the whole record, as Harvey almost caricatures the woman with didactic purpose. Hope Six causes a level of questioning discomfort that Let England Shake never provoked: “is Harvey’s guilt at the beggar-boy’s pleading for “Dollar, Dollar” ultimately more significant or insightful than any other tourist’s?”, Andy Gill asks. In some respects, Harvey’s subject is bludgeoningly apparent: what she records is not always subtle. In ‘A Line in the Sand’, she sings:

This seems too blunt to be affecting, but the italics suggest that it’s another instance of quotation. Harvey then turns it into an eerily high, deceptively cheery refrain that becomes frailly unnerving, creating a tension between musical lightness and lyrical despair: “What I’ve seen – yes, it’s changed how I see humankind”. In ‘The Ministry of Defence’, thrillingly heavy guitars build up apocalyptic excitement, but the details Harvey records are troubling, paraphrasing T. S. Eliot’s ‘The Hollow Men’, Not with a bang but a whimper:

This “biro pen” seems too flimsy to scratch into the wall, viscerally pushing the implement to breaking point, scoring its nib into plaster and brick.

Harvey has always pushed at the edges of her own expertise. White Chalk (Island Records, 2007) featured self-taught piano, as the guitar had become over-familiar; she reinvented her voice from the deep heart-throb of To Bring You My Love (Island Records, 1995) to an almost unearthly reed. Performing Let England Shake, she seemed to recede from her own stage presence, staying very still, channelling otherness. Her newest solo instrument is the written word. Interviewed in 2011, she stated that she wrote Let England Shake initially unaccompanied by music: “with such weighty subject matter, it [the album] needed to work at that very root level, or it was gonna fall apart completely”. In calling her lyrics the “root” of “weighty subject matter”, Harvey imbues written composition with an elegiac sobriety. In Seamus Murphy’s films for Let England Shake, portions of text are read aloud, often by readers who seem unaccustomed to them, so that each song becomes estranged, simultaneously heard and seen through subtitles (creating a doubling of “Time” and “Thyme” in ‘On Battleship Hill’). Murphy creates visually poetic contrasts alongside Harvey’s lyrics: a ferris wheel, brightly illuminated, through dark trees. Changing light on a sparse hilltop. The sound of the wind. The written word begins to precede other mediums despite, or precisely because, it doesn’t come easily:

I find writing very difficult. I always have done. And particularly after the last four or five years, I’ve become much more interested in writing words. Some may just be poems or short prose, some may become songs. Some don’t. But I’ve given it a lot of study and I work very hard at it. I work every day, […] This, in some ways, feels like the start of a whole body of work yet to come.

In The Hollow of the Hand, music is displaced by tears: “And sounds of weeping came instead of music / And I walked out trembling and pushed my face into the soil”. Harvey’s poems and Murphy’s photographs depict ambiguous aftermaths of tragedy, as well as imparting something of the rhythm of daily life. ‘The Abandoned Village’ is a ghost story of sorts:

This seems to presage the “girl who runs and hides” in ‘The Ministry of Defence’, as if the girl ducks out of view in the poem and reappears in the song, moving in and out of hiding places in Harvey’s work. The “pock-marked walls” suggest gunfire, perhaps, and “hung from the ceiling” could also become ominous. Eventually, she finds a photograph of what seems to be the girl she is looking for, but “her mouth is missing”, flaked away from the image, “a white nothing.” This flaking away refers to the photograph, but also evokes spectres of bodily mutilation. Harvey calls on the corn doll, the photograph, and a tree outside as mute witnesses, as if the visible and the vocal have changed places: italics potentially suggest quotations, sung refrains, and ghostly address, the letters leaning into the blank of the page. Murphy’s photographs have no captions, so the history of their moments can only be guessed at: they tell no tales. The Hollow of the Hand is anti-narrative, refusing to string individual elements into explanation.

To some extent, Harvey’s songs recreate absent contexts for the poems. ‘Where it begins’ pairs with the lyrics of ‘The Wheel’:

The poem makes no direct mention of massacre, so the ambiguous ‘28,000’ statistic in the song creates a new haunting: “squeals in the heat” suddenly seems more violent than the squeaks of a fairground ride, as the song transforms children’s bodies at play into “faces, limbs, a bouncing skull”. It’s unclear whether Harvey always intended poem and song to converse: ‘Medicinals’, ‘Chain of Keys’, ‘Near the Memorials to Vietnam and Lincoln’, ‘The Orange Monkey’ and ‘Dollar, Dollar’ also pair with poems in The Hollow of the Hand, often under different titles.

Harvey’s earnestness has never precluded humour: she somehow manages to be intensely serious and wry at the same time. She splices the devices of riddles and ballads with shamanic elements in ‘The Orange Monkey’:

Why a monkey? Is this a guide, or a trickster? The first two lines are reminiscent of Emily Dickinson’s “I felt a Cleaving in my Mind – / As if my Brain had Split – / I tried to match it – / Seam by Seam: / But Could not make them fit –”. Harvey might set out on her quest, but the track is “uneven”; “I took a plane to a foreign land” doesn’t scan easily within the four-stress verse. Can you travel back in time by getting on a plane to Afghanistan, Washington, or Kosovo? In the song, clicking percussion mimics the sound of a circling wheel.

As well as wheels of time, The Hollow of the Hand is full of, well, hands, praying and enclosing, open and curled into fists: they appear in both Harvey’s poems and Murphy’s photographs, in extended supplication:

What is on the paper – if anything – is not read. In ‘Throwing Nothing’, “a boy throws out his hands / to feed the starlings. / But he’s throwing nothing; / it’s just to watch them jump.” Harvey’s poems also “throw nothing”, fascinated by spaces at the heart of social contact (the hollow of the hand, quite literally). In the accompanying song, ‘Near the Memorials to Vietnam and Lincoln’, the boy seems to summon a crowd of tourists alongside the birds, then “a black man in overalls” opens a door to the “underworld”. The song is more heightened than its page-bound counterpart, like a séance gone wrong. Mirroring the starlings, the tourists gather and respond to emptiness, the space of the dead.

In one of Murphy’s photographs, a pair of hands which are purpling – perhaps dead – clutch at a bunch of green leaves; in another, a boy lies on dirt, one of his fists lightly enclosing grains of it. In ‘Zagorka’, an old woman refuses to allow entry into a Kosovan church: “Both keys move into a fist.” I sympathise with the old woman’s reluctance, as well as the poet’s unease: Harvey’s speakers could be emotional vampires, asking to be invited in, although their intentions are humane rather than bloodthirsty. Her poems clutch for moments of connection: they feel lonely and curious, even when they’re channelling other voices through italics and quotations. If she is a war poet, she implicitly wants to reveal collective trauma: but her speaker also, in ‘The Orange Monkey’, seeks to ease “restlessness” in her own brain.

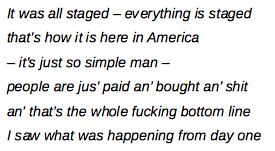

One poem, titled ‘A Guy Who Knows What the Fuck’s Going On’, frantically addresses the reader:

Harvey doesn’t offer any commentary, just allows the character to speak, with an edge of charismatic humour. Some of the most effective poems in The Hollow of the Hand contain seemingly-direct speech like this, although the voices skip and jump, as if the transmission is interrupted. ‘Pity for the Old Road’ is entirely enclosed in quotation marks. A speaker remembers a tree-lined road from their childhood that has become urbanised over time:

Harvey’s poems may be too sparse for some tastes, but they give “a bit of a feeling”. They combine apparent directness with extreme privacy, their subjects caught only fleetingly. Murphy’s photographs are beautiful, and similarly understated.

Above all, Harvey echoes Wordsworth’s Lyrical Ballads (1798–1800): queer, playful hauntings. Her work contains a similar tension between empathy and distance, and a dissonance between observation and hallucination. Figures become spirited in an instant. In the song ‘Dollar, dollar’ (titled ‘The Glass’ in The Hollow of the Hand), the face of a begging child hovers in the mirror of her car:

The locked box of the car echoes ‘The Ministry of Social Affairs’, in which “the money–changers sit / by their locked glass cabinets”, shadowed by “a million beggars’ silhouettes”. It’s clear where Harvey’s sympathies lie, but sitting on the other side of the glass, she becomes a “money-changer” herself. The glass is like a photographic plate or reel of film, the boy’s face transposed on to it, “pock-marked” like the walls in ‘The Abandoned Village’. The change from “rear-view glass” to “mirror glass” implies that the boy’s hollow visage could be transposed over Harvey’s own face in uncomfortable self-recognition, as her words are “swallowed” by vision.

In ‘The Wheel’, “a tableau of the missing / tied to the government building” is slowly bleached in the sun:

There is indeed a collection of photographs by the Government Building in Kosovo, depicting ethnic Albanians who disappeared in the 1999 Kosovo war. [2] Harvey’s ‘28,000’ doesn’t match the real number of photographs: she may be combining different atrocities. In ‘Dollar, dollar’, the mental image of the boy’s face refuses to be erased; here, the slow effacement of the photographs is equally implacable and haunting.

One of Harvey’s influences in recent years is the work of Harold Pinter. [3] His lecture on ‘Art, Truth and Politics’ (2005) could represent the ambitions of both The Hollow of the Hand and The Hope Six Demolition Project:

More often than not you stumble upon the truth in the dark, colliding with it or just glimpsing an image or a shape which seems to correspond to the truth, often without realising that you have done so. But the real truth is that there never is any such thing as one truth to be found in dramatic art. […] Sometimes you feel you have the truth of a moment in your hand, then it slips through your fingers and is lost.

[…]

Political theatre presents an entirely different set of problems. Sermonising has to be avoided at all cost. Objectivity is essential. The characters must be allowed to breathe their own air. The author cannot confine and constrict them to satisfy his own taste or disposition or prejudice. He must be prepared to approach them from a variety of angles, from a full and uninhibited range of perspectives, take them by surprise, perhaps, occasionally, but nevertheless give them the freedom to go which way they will. This does not always work.

It’s doubtful whether Harvey really avoids “sermonising”, but I don’t doubt her earnest commitment to these dramatic principles, creating political theatre through poetry, music, song, film and performance. “I’m not putting forward my own opinion, but you’ll probably find it in the spaces in between”, she stated in 2011.

Moving from poem to song, she creates many of these “spaces in between”, filled by music, seeping through the cracks. This rising tide takes what might seem banal or desensitised in Harvey’s lyrics and remystifies it. In ‘River Anacostia’, her plaintive voice echoes alongside the collective chorus of an old spiritual: “Wade in the water”, they sing, “God’s gonna trouble the water”. This draws on John 5:3 and 5:4, in which an angel comes to a “great multitude of impotent folk” by a Jerusalem pool, “blind, halt, withered, waiting for the moving of the water”:

For an angel went down at a certain season into the pool, and troubled the water: whosoever then first after the troubling of the water stepped in was made whole of whatsoever disease he had.

(King James Bible)

As Harvey’s lyrics note, the Anacostia River is heavily polluted, unlikely to cure anyone in its present state, channelling murky unease through The Hope Six Demolition Project:

Oh, my Anacostia –

do not sigh, do not weep –

– she leaves the water troubled in her wake.

[1] Unless otherwise indicated, I quote lyrics as they are represented on PJ Harvey’s website. In the recorded songs, Harvey sometimes creates variants and additions to these lyrics.

[3] Harvey told Pitchfork: “I had to find a way into the language I wanted to use. I […] found myself reading a lot of Harold Pinter’s work, actually– not just his plays, but his political essays and his poetry. There’s a contemporary playwright who I greatly admire called Jez Butterworth, and I saw a play of his called Jerusalem which I was quite affected by. And I was looking at artwork like Goya’s “Disasters of War” series and Salvador Dali’s pictures from the Spanish Civil War era. I was watching a lot of Stanley Kubrick movies, particularly Paths of Glory, 2001: A Space Odyssey, and Barry Lyndon. All of these things somehow go into a big melting pot inside of me and come out in my own way.”

[4] This collective refrain is not in the official lyrics, only heard in the recorded version.

Leave a Reply