100 Dutch-Language Poems: From the Medieval Period to the Present Day, selected and translated by Paul Vincent and John Irons (Holland Park Press, London 2015)

by Richie McCaffery

I often look forward to anthologies of translations as a way of introduction to a culture, language and poetry I might not have come across or really considered before. An extra dimension is added to the pleasure of reading this particular anthology because I am slowly trying to learn Dutch since moving to West Flanders, Belgium a few months ago and have often looked for a good anthology that shows the various literary movements and history of Dutch-language poetry. It is important to note at this early juncture that this anthology concerns Dutch-language poems, which encompasses the poetries of Flemish-speaking areas of Belgium and The Netherlands equally. While there are certainly cultural differences between both countries, this anthology serves to show how these countries share a language, albeit with disparities in terms of pronunciation. The overall effect is one of cultural distinctiveness twinned with the occasional cross-border collaboration between Flemish and Dutch poets, such as Hugh Claus, a Flemish poet but high-profile member of the Dutch/Flemish avant-garde art movement CoBrA.

I was pleased at times, while reading the poems in this anthology, to be able to compare the English translation with the Dutch/ Flemish original, in the case of poets renowned for writing luminously clear verse, such as Remco Campert (b.1929), who is a Dutch poet I have read in English translation for years (he has been translated into English since the 1960s) before coming to Belgium, and who here celebrates the cross-border, international companionship poetry brings:

This translation is by Paul Vincent. Together with John Irons, both men have strong academic links to Dutch-language poetry, but are also poets themselves, and this is shown in this translation which does not seem to slavishly follow Campert’s original, as the final line of the third stanza in Campert’s original refers to an earth that asks, instead of ‘needs’. Both Vincent and Irons have selected, curated and translated (separately) all of the poems in this anthology with the exception of a handful of particularly famous or successful translations as those by James S. Holmes, the late American translator who pioneered the discipline of translation studies. In the poem above Campert engages in a meta-poetic discourse that I will return to later, a distinctive feature that marks out a lot of modern Dutch-language poetry. I must point out that my interest in this anthology is as a learner of the language and as an introduction to the poetries of these two countries, not as a literary historian or a translation scholar. As such, I confess my nescience when it comes to early Dutch poetry, and I note in the editors’ introduction that they give a nod towards a previous anthology (Dutch Poetry in Translation: Kaleidoscope, 1998), only to say that its choice “in later periods is conservative.” On the surface, this anthology seems to contain earlier, canonical texts twinned with a more adventurous later, or modern, selection. The editors begin their history of Dutch-language poetry in 100 poems with ‘All Birds Are A-Nesting’ (translated by John Irons) – an anonymous koan-like or haiku-like fragment from the 11th century, which is extremely famous as the first extant Dutch-language poem, so famous that Dutch and Flemish students can often recite it by heart:

The brief but informative introduction lays out the various movements, styles and themes of these poems and the history of Dutch-language poetry, with the anthology unfolding chronologically, moving from the poetry of amour courtis and the ballad, through Romanticism, Aestheticism, Modernism to the more socially realist or surrealist ‘Fiftiers’ poets, the Pink poets of the 1960s and 1970s through to the modern-day media poems, informed by events such as the assassination of Theo van Gogh, Pim Fortuyn and the attempted assassination of Queen Beatrix in 2009. The youngest Dutch poet represented here is Lieke Marsman (b.1990) who seems to continue Belgian poet Hugo Claus’s (1929-2008) legacy for precocity in terms of early appearance in print. However, Marsman’s poem has more in common with Claus’s near contemporary, and arguably one of the finest poets in this selection, Belgian Herman de Coninck (1944-1997), whose work is characterised by a linguistic dexterity, cleverness, tenderness and innate sensuousness. I compare Netherlands poets writing in Dutch with Flemish poets, in the spirit of Campert’s poem, that poetry, and indeed translations, should break down barriers while also retaining a sense of cultural identity. The fact that a number of the poets in this anthology were associated with art and literary movements that brought the two countries together suggests that there is no sense of literary or linguistic exclusivism here, that poetry by Netherlands and Belgian writers are enjoyed equally in both countries, and increasingly, with the aid of such translations, further abroad. Here is an extract from Lieke Marsman’s ‘Big Bang’ in Paul Vincent’s translation:

Note how Marsman comments on the composition of her tactile imagery in the poem itself, rather like the meta-poetic poem of Remco Campert above, and then compare that with this extract from Herman de Coninck’s poem ‘Yonder’ (in Vincent’s translation):

While the selection of 20th century poets is certainly exciting, leading to many new discoveries, it is a shame to note what I feel are some glaring omissions in this anthology. The editors admit in their introduction that the 100-poem format had its constraints and that it would inevitably lead to a subjective selection, but I feel there are poems here that lean towards the weaker end of the spectrum. Take for instance this extract from ‘Blues On Tuesday’ by Dutch performance poet Jules Deelder (in Vincent’s translation):

While the selection of 20th century poets is certainly exciting, leading to many new discoveries, it is a shame to note what I feel are some glaring omissions in this anthology. The editors admit in their introduction that the 100-poem format had its constraints and that it would inevitably lead to a subjective selection, but I feel there are poems here that lean towards the weaker end of the spectrum. Take for instance this extract from ‘Blues On Tuesday’ by Dutch performance poet Jules Deelder (in Vincent’s translation):

Deelder’s work seems to be a triumph of style over substance, and although such poems show us the range in subject matter of poetry written in Dutch, I find it regrettable that no room could be found for poets who I have already encountered in translation, whose work I would consider first-rate. One of these is the Flemish poet Eddy Van Vliet (1942-2002) whose spare, limpid work on human relationships places him easily in the same category as Hermann de Coninck. One of the desirable effects of an anthology such as this is to get the reader to think about which poet they wish to remember, read again and seek out and it is always good to have a diverse selection that does not lean too heavily on the canonical. That said, I feel Deelder’s poem could have been removed on the basis of quality alone to make room for a poem by the Dutch poet Jan G Elburg (1919-1992) who I feel writes some of the most moving, playful and tender poetry in Dutch and translation. Here is an extract from ‘a talent for this’ as translated by André Lefevere, the noted Belgian translation theorist (1945-1996), whose work of rendering Dutch-language poetry into English seems a vital act of literary and cultural conveyance to new audiences and the fact that he chose to translate Elburg alludes to his importance as a poet:

Deelder’s work seems to be a triumph of style over substance, and although such poems show us the range in subject matter of poetry written in Dutch, I find it regrettable that no room could be found for poets who I have already encountered in translation, whose work I would consider first-rate. One of these is the Flemish poet Eddy Van Vliet (1942-2002) whose spare, limpid work on human relationships places him easily in the same category as Hermann de Coninck. One of the desirable effects of an anthology such as this is to get the reader to think about which poet they wish to remember, read again and seek out and it is always good to have a diverse selection that does not lean too heavily on the canonical. That said, I feel Deelder’s poem could have been removed on the basis of quality alone to make room for a poem by the Dutch poet Jan G Elburg (1919-1992) who I feel writes some of the most moving, playful and tender poetry in Dutch and translation. Here is an extract from ‘a talent for this’ as translated by André Lefevere, the noted Belgian translation theorist (1945-1996), whose work of rendering Dutch-language poetry into English seems a vital act of literary and cultural conveyance to new audiences and the fact that he chose to translate Elburg alludes to his importance as a poet:

I know that I really shouldn’t carp about what is essentially an excellent anthology of translations, but I’d also like to make it known that a wealth of equally gifted Dutch and Flemish poets exist in translation outside of this anthology, and reading this anthology has inspired me to seek them out again, as well as some new discoveries. As I have already said, I can connect with this anthology on a deeper, linguistic level as a learner of the language than other translation anthologies that I have purely accessed for their English translations. This forces me to defer to and reconsider the original and not a stand-alone English translation. I have surprised myself in reading this anthology by the amount of poems I could understand in Dutch / Flemish first and how I have noticed subtle differences between the phrasings in the original and the English translation. The purpose of all such poetry anthologies must first be making accessible the poetic riches of a certain country (or countries, in this case) to a new or unaware audience. This breaks down barriers and opens up the world, but only to a certain extent, as the original version must always be the ‘verbal icon’ or a work, in André Lefevere’s words, of ‘pristine purity’ of which a translation is only ever a ‘refraction’. That said, a good translation, in the case of those in this anthology, is always a desirable faute de mieux but a casual reader, myself included, should never blinker themselves to the original on the opposite page. I feel this book has reached me at just the right time and has even served as a learning aid, and the anthology permits a great many reading styles, from purely English reading to more profound, scholarly readings of the poetry.

Despite my slight grumbles about poets I would like to have seen represented here, the major poets whose name and work carries outside of Belgium and the Netherlands, such as Gerrit Komrij (1944-2012), Lucebert (1924-1994), Hugo Claus and Paul van Ostaijen (1896-1928), are all represented with famous examples of their work. For instance, Hugo Claus’s ‘In Flanders Fields’ is about the most anthologised Dutch-language poem I can think of, appearing in every book of Claus’s poems in translation as well as in the fascinating 1998 anthology commemorating the Great War, Low Leans the Sky. The poem, as translated by John Irons, deals with the uneasy legacy of Belgium as the killing fields of Europe and how the land has been fertilised by the tremendous loss of life:

Paul van Ostaijen, Belgium’s major proto-Modernist poet, is represented by ‘Melopee’, a poem about the moon, river and a rower upon the river moving out to sea. It is an enchanting poem, but I feel that if Van Ostaijen is to be given a small poem, since many of his poems are longer and experimental, then perhaps the Imagist purity of ‘The Sailor’s Suicide’ might be more immediate and effective; here it is in James S. Holmes’s (the American translation academic and pioneer of Gay Studies in the Netherlands) translation:

The idea that sailors die in pursuit of sirens is nothing new, but it is the introduction of time, symbolised in such a mundane, non-mythic way as a glance at a watch, which elevates this poem to something singular and arresting. In the original, Flemish version, Ostaijen seems to be talking about, or trying to explain, the suicides of sailors, whereas Holmes’s translation turns this into an eerie, one-off event. This reminds me of the distinctions to be made between descriptivist and prescriptivist approaches to translation, and Holmes argued for a middle ground between both. Here he follows the poem closely, but also puts a different inflection on it, thus making it its own poem. What I do like about Vincent and Irons’s translations in this anthology is a similar middle-place reached between faithfulness to the original and a knowledge that an English rendering will always become its own and separate poem.

The idea that sailors die in pursuit of sirens is nothing new, but it is the introduction of time, symbolised in such a mundane, non-mythic way as a glance at a watch, which elevates this poem to something singular and arresting. In the original, Flemish version, Ostaijen seems to be talking about, or trying to explain, the suicides of sailors, whereas Holmes’s translation turns this into an eerie, one-off event. This reminds me of the distinctions to be made between descriptivist and prescriptivist approaches to translation, and Holmes argued for a middle ground between both. Here he follows the poem closely, but also puts a different inflection on it, thus making it its own poem. What I do like about Vincent and Irons’s translations in this anthology is a similar middle-place reached between faithfulness to the original and a knowledge that an English rendering will always become its own and separate poem.

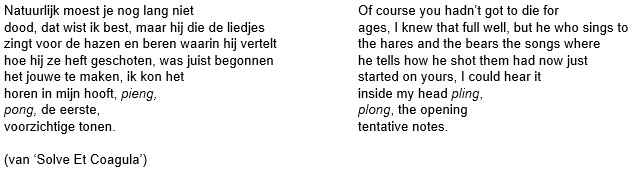

One of the main positives to flag up about this anthology is the scope it offers for new discoveries. For every poet I see as being unfairly neglected, there are other poets I had not heard of that are included, and often as you read the collection you become aware that you are in the presence of a remarkable aesthetic, particularly in the mid to late 20th century poetry, which draws upon surrealism. For example, there is Eva Gerlach’s (b.1958) ‘Solve Et Coagula’ (in Irons’s translation) that deals eerily with the onset of a fatal illness, in the form of a nosebleed that will not stop:

I’d like to now turn to the afterword in the anthology, an academic essay by Gaston Franssen entitled ‘A Topography of Dutch Poetry’. The essay is to be praised for arguing that we must break out of our misconception of “the narrowness of the Netherlands (and thus, supposedly, of its people)” and move away from a vision of the place as one of unrelieved flatness and greyness. Franssen argues cogently for the poetry in this anthology, and certainly it goes a long way in proving the multiplicity and diversity of poetic voices in Belgium and the Netherlands, but one strand of the argument struck me as being very close to language use in Scottish literature. First of all, it is a linguistic fact that Flemish, Dutch, and Scots share many similarities, such as overlaps or sonic coincidences in the lexicon: “kirk” for church, “ken” for know, and armpit, which is “oksel” in Dutch and “oxter” in Scots, ‘leid’ which is a lyric in Scot, or a song in Dutch. These are just a few examples off the top of my head; the list is endless. I was also struck by how redolent some of these poems were of others I had read in the past. For instance, Erik Spinoy’s (b.1960) ‘At the Jewish Cemetery’, (Irons’s translation), reminded me deeply of Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘At My Father’s Grave’:

I’d like to now turn to the afterword in the anthology, an academic essay by Gaston Franssen entitled ‘A Topography of Dutch Poetry’. The essay is to be praised for arguing that we must break out of our misconception of “the narrowness of the Netherlands (and thus, supposedly, of its people)” and move away from a vision of the place as one of unrelieved flatness and greyness. Franssen argues cogently for the poetry in this anthology, and certainly it goes a long way in proving the multiplicity and diversity of poetic voices in Belgium and the Netherlands, but one strand of the argument struck me as being very close to language use in Scottish literature. First of all, it is a linguistic fact that Flemish, Dutch, and Scots share many similarities, such as overlaps or sonic coincidences in the lexicon: “kirk” for church, “ken” for know, and armpit, which is “oksel” in Dutch and “oxter” in Scots, ‘leid’ which is a lyric in Scot, or a song in Dutch. These are just a few examples off the top of my head; the list is endless. I was also struck by how redolent some of these poems were of others I had read in the past. For instance, Erik Spinoy’s (b.1960) ‘At the Jewish Cemetery’, (Irons’s translation), reminded me deeply of Hugh MacDiarmid’s ‘At My Father’s Grave’:

Here is an extract from Hugh MacDiarmid’s poem for comparison:

The sunlicht still on me, you row’d in clood,

we look upon each ither noo like hills

across a valley. I’m nae mair your son.

It is my mind, nae son o’yours, that looks,

and the great darkness o’ your death comes up

and equals it across the way.

One potential strand for future development could be the rendering of Scots poems into Dutch and Dutch-language poems into Scots, as I feel this would be more linguistically close than into standard English. While I am tentatively trying to show a certain kinship between Scottish and Dutch-language poetry, one of the main strands of Franssen’s argument seems to be about duality. Franssen centres his attention on one of the most famous poems in Dutch, H. Marsman’s (1899-1940) ‘Memory of Holland’ where both a wondrous and dismal image of Holland is conjured up at the same time, as place of bucolic bliss and the endless danger of “the water” with “its endless disasters” which “is feared and obeyed.” Franssen ventures that

Dutch poetry, even though it springs from a culture famous for negotiation and compromise, reveals two extreme, incompatible views with regards to the self-image of the Netherlands. A middle ground seems non-existent: the country and its landscape are either admired or loathed.

One is reminded perhaps of Hugh MacDiarmid’s famous drunk man’s rallying cry that he would “ha’e nae hauf-way hoose, but aye be whaur / Extremes meet.” But the concept of duality, or torn identity is a thorny issue. I am thinking particularly of a very witty issue of the almost samizdat Edinburgh literary periodical One O’Clock Gun where “duality” was called “Edina’s plague” and figures like Kevin Williamson were calling for duality to “come in, your time is up.” It does seem to be a dialectic that has been ridden to death, resurrected and ridden to death again. I think duality is a feature central to any literature; wherever you have poets, you will have them considering the existential and practical pros and cons of their locale or topography, so to make a special claim for Scots or Dutch-language, poetry on these grounds seems erroneous. Yet, there seems to be a certain closeness, linguistically speaking between the nations in case, as well as similarities in the poetry and poetic movements. To recap, this is the first anthology that has urged me to really consider the purity of the original, looking for instant access to English translations. The translations themselves reach a compromise between descriptivist and prescriptivist, or faithful, renderings, reminding me that the translation is a new poem in itself, not the illusion of the original poem transplanted into standard English. I have enjoyed the dialogue this anthology has allowed me to have, from embracing certain poems to disagreeing with other selections or points made. This anthology goes a long way to fill the lacuna of anglocentric misunderstanding regarding the Low Lands as a largely uneventful place – this anthology proves that is simply not the case, and many of these poets have been closely guarded secrets in English translation for many years. Hopefully not for much longer.

Leave a Reply