I’m a little behind on my main pick for read of year: as many GRB readers will be well aware, Maggie Nelson’s remarkable memoir and work of “auto theory” The Argonauts (Graywolf Press) came out in 2015. Yet it is the book so many of my friends have read and wanted to talk about in 2016 – a copy with countless folded down corners always in someone’s hand, pocket, or bag; a book always raised in conversations over coffee and, even more animatedly and enthusiastically, over beers. It’s certainly the book that I’ve returned to and thought about most frequently over the last twelve months. And, alas, many of its central themes – the radical, queer possibilities of love, companionship, friendship and family making; the potential fluidity of gender; living in a world that, as Nelson writes, is “frantic for resolution” when knowing “that sometimes the shit stays messy” – have come into yet sharper focus in a year when so many forms of self-righteous ignorance, intolerance and reactionary rage have been in the ascendency. So many passages bear reading again and again. For me, maybe most of all, is the section where Nelson writes about the difficulties of intimacy and dependency, moving from a quote from Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor’s On Kindness to the lasting effects of her difficult relationship with her mother: “I … have to be alert for the tendency to treat other people’s needs as repulsive. Corollary habit: deriving the bulk of my self-worth from a feeling of hypercompetence, an irrational but fervent belief in my near total self-reliance”. Imagine being half as good at writing as Maggie Nelson is.

I’m a little behind on my main pick for read of year: as many GRB readers will be well aware, Maggie Nelson’s remarkable memoir and work of “auto theory” The Argonauts (Graywolf Press) came out in 2015. Yet it is the book so many of my friends have read and wanted to talk about in 2016 – a copy with countless folded down corners always in someone’s hand, pocket, or bag; a book always raised in conversations over coffee and, even more animatedly and enthusiastically, over beers. It’s certainly the book that I’ve returned to and thought about most frequently over the last twelve months. And, alas, many of its central themes – the radical, queer possibilities of love, companionship, friendship and family making; the potential fluidity of gender; living in a world that, as Nelson writes, is “frantic for resolution” when knowing “that sometimes the shit stays messy” – have come into yet sharper focus in a year when so many forms of self-righteous ignorance, intolerance and reactionary rage have been in the ascendency. So many passages bear reading again and again. For me, maybe most of all, is the section where Nelson writes about the difficulties of intimacy and dependency, moving from a quote from Adam Phillips and Barbara Taylor’s On Kindness to the lasting effects of her difficult relationship with her mother: “I … have to be alert for the tendency to treat other people’s needs as repulsive. Corollary habit: deriving the bulk of my self-worth from a feeling of hypercompetence, an irrational but fervent belief in my near total self-reliance”. Imagine being half as good at writing as Maggie Nelson is.

J. Demos’ Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Sternberg Press, 2016) is an expansive critical foray into the relationship between contemporary art, theory, politics and ecology. Demos, professor of Art History at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and director of its Center for Creative Ecologies, covers a lot of ground, thematically and geographically. In a series of brilliant case studies traversing the Maldives, Arctic, Mexico and India, as well as Europe and North America, Decolonizing Nature connects a wide array of artistic-activist practices and theoretical materials from the Global South and North; the recent “material turn” and the various object-oriented ontologies of literary and cultural studies are considered alongside Indigenous systems of thought, for instance, as Demos synthesises modes of thought and action that share an interest in formulating a post-anthropocentric world. Eschewing the climate catastrophism and nihilism of a popular media that revels in CGI images of loss and destruction, Demos emphasises the role contemporary art can play in the resistance to neoliberalism and neocolonialism. As Demos succinctly puts it in the book’s opening pages,

J. Demos’ Decolonizing Nature: Contemporary Art and the Politics of Ecology (Sternberg Press, 2016) is an expansive critical foray into the relationship between contemporary art, theory, politics and ecology. Demos, professor of Art History at the University of California, Santa Cruz, and director of its Center for Creative Ecologies, covers a lot of ground, thematically and geographically. In a series of brilliant case studies traversing the Maldives, Arctic, Mexico and India, as well as Europe and North America, Decolonizing Nature connects a wide array of artistic-activist practices and theoretical materials from the Global South and North; the recent “material turn” and the various object-oriented ontologies of literary and cultural studies are considered alongside Indigenous systems of thought, for instance, as Demos synthesises modes of thought and action that share an interest in formulating a post-anthropocentric world. Eschewing the climate catastrophism and nihilism of a popular media that revels in CGI images of loss and destruction, Demos emphasises the role contemporary art can play in the resistance to neoliberalism and neocolonialism. As Demos succinctly puts it in the book’s opening pages,

[m]y conviction is that environmentally engaged art bears the potential to both rethink politics and to politicize art’s relation to ecology, and its thoughtful consideration proves nature’s inextricable binds to economics, technology, culture, and law at every turn.

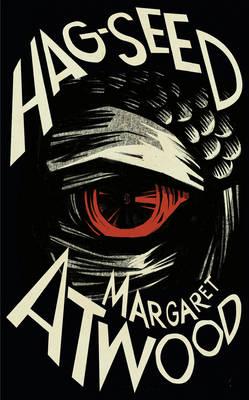

For my final pick, I found it impossible to decide between Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed (Penguin Random House, 2016) and Ilja Trojanow‘s The Lamentations of Zeno (Verso, 2016). The former is an ingenious and thoughtful retelling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Trojanow‘s work, translated into English by Philip Boehm, is the story of an aging glaciologist reluctantly working as a travel guide aboard an Antarctic cruise ship. Regaling the ship’s wealthy passengers with details of the decline and disappearance of his beloved glaciers, he begins to plan a startling gesture to rouse them from their indifference to the rapidly disappearing environment at this isolated corner of the globe. There are a number of parallels between the two – not just in their narratives of central figures cast adrift in one way or another, and of the pain of loss and plans unfulfilled, but also their deft prose and the lightness with which both writers wear their considerable learning, in the service of narratives that are at once subtle, humorous and poignant.

For my final pick, I found it impossible to decide between Margaret Atwood’s Hag-Seed (Penguin Random House, 2016) and Ilja Trojanow‘s The Lamentations of Zeno (Verso, 2016). The former is an ingenious and thoughtful retelling of Shakespeare’s The Tempest. Trojanow‘s work, translated into English by Philip Boehm, is the story of an aging glaciologist reluctantly working as a travel guide aboard an Antarctic cruise ship. Regaling the ship’s wealthy passengers with details of the decline and disappearance of his beloved glaciers, he begins to plan a startling gesture to rouse them from their indifference to the rapidly disappearing environment at this isolated corner of the globe. There are a number of parallels between the two – not just in their narratives of central figures cast adrift in one way or another, and of the pain of loss and plans unfulfilled, but also their deft prose and the lightness with which both writers wear their considerable learning, in the service of narratives that are at once subtle, humorous and poignant.

Online

Bee Wilson’s account of the intriguing history of the meal replacement pill is well worth a read. So too is Tobias Jones’ “Inside Italy’s ultras: the dangerous fans who control the game”. Jones meticulously recounts the rise and fall of Raffaello Bucci, an influential Juventus “ultra”, a man for whom the love of a football club spiralled out of control as he became imbricated in a dangerous world of racketeering and organised crime.

In this most eventful of years, so many consistently thoughtful, clear voices have spoken out. In the run up to the 23rd of June, the ever astute and eloquent James Butler offered a prescient analysis of the crises facing Europe and the success of the right in transforming the United Kingdom’s EU referendum into a proxy vote on immigration. Immediately following the referendum, the London Review of Books’ “Where are we now?: Responses to the Referendum” provided a good range of reaction and analysis (and a number of worried glances towards the upcoming election in the United States). While I disagree with their decisions to vote “Yes” that day, T. J. Clark’s contribution is an important reminder that, as Tariq Ali had earlier written, there were very many “good socialist reasons” for voting Leave. As Clark noted, “[w]hat Dijsselbloem and Schäuble did to Greece” between 2008 and today was “an indication of what the EU was truly for. It remains our best clue to how ‘Europe’ would act if a left government, of a nation less hopelessly enfeebled than post-Pasok Greece or post-Blair-and-Brown Britain, dared, say, to resist TTIP’s final promulgation of the neoliberal rule of law.”

In the months following the referendum there was a spike in reported incidents of racist and anti-immigrant attacks, harassment and vandalism (and let us never forget that Arkadiusz Jóźwik was killed by a group of six teenagers in Harlow, after they heard him speaking Polish on the phone). In October, James Butler wrote of how a comparable spike in homophobic attacks following the referendum could be understood as part of a broader resurgence of an “old-school authoritarian nationalism with its emblem in the lamprey-like grin of Nigel Farage”. Butler argues, compellingly, that for many who voted for Brexit, “taking back control” was never just about the European Union, but was a legitimation for “a whole host of fantasies about unravelling the social direction of the past fifty years”.

It is a testament to the force and frequency of the traumas that have beset 2016 that, in the aftermath of the Brexit vote, David Cameron, perhaps the worst PM the United Kingdom has ever seen, was able to slip away so quietly after his resignation. In a series of pieces for The Guardian and the LRB, Dawn Foster wrote incisively on Cameron’s successor, Theresa May. “Citizens of the world, look out”, written shortly after May’s inaugural speech as leader at the Conservative Party Conference, is a characteristically witty and perceptive account of that event (I would also strongly recommend Foster’s brilliant book Lean Out, which was released in January).

In the wake of events in early November in the United States, a number of pieces provided important responses to the election of Donald Trump and all that it has unleashed. Jeffrey J. Cohen’s “The Story I Want to Tell” narrates the meeting of the National Policy Institute in Washington DC in the weeks following the election. The innocuously named NPC is a white supremacist, Neo-Nazi organisation: images and videos circulated online of its meeting, with some audience members using the Nazi salute and another shouting “Heil the people! Heil victory!”. As Cohen details, though, Joseph Goldstein’s New York Times piece that had originally reported the NPC’s meeting neglected to mention that it was met “with unremitting protest” by a great many noisy, placard-bearing protestors outside the venue, who eventually succeeding in cutting the meeting short. Protest and resistance can take a great many forms, as the moving final paragraph to Cohen’s piece also makes clear.

As someone who recently finished writing a PhD thesis about medieval literature and the various ways it has come to be archived, mediated and remade in the postmedieval age, I have been particularly interested in responses to this year’s events that have engaged with a broader historical arc. After all, central to so much of the rhetoric and imagery of far right and white supremacist movements on both sides of the Atlantic is an appeal to an illusory history, one in which “European” values and culture have been degraded by a modern world of multiculturalism and political correctness. This is a simple yet powerful story of an inherently superior race regaining what has been lost (the leader of the NPC, for example, has stated that America belonged to “white people … a race of conquerors and creators”). The classical and medieval periods play important roles in these stories, so often rendered as entirely white and overwhelmingly masculine worlds. In its tracing of the eventful adolescent years of Derek Black, Eli Saslow’s excellent “The White Flight of Derek Black” traces the importance of education and friendship in the life of a young man who was, at one time, the precocious heir apparent to America’s white nationalist movement. Crucial to Black’s gradual repudiation of his views are his studies in medieval history at a small liberal arts college in Florida. From his studies of the eighth to twelfth centuries in particular, Black realises that “Western Europe had begun not as a great society of genetically superior people but as a technologically backward place that lagged behind Islamic culture”. ““We basically just invented [modern concepts of race and whiteness]”” Black concludes, as he comes to see what many have long tried to emphasise about the Middle Ages especially and history more generally: the past contains heterogeneity and complexity, not easy stories that legitimise claims to supremacy.

In a similar vein, a number of pieces have made powerful calls for interventions by historians and literary critics, both in discussions that take place in their own academic communities and beyond. Donna Zuckerberg’s “How to Be a Good Classicist Under a Bad Emperor”, Sierra Lomuto’s “White Nationalism and the Ethics of Medieval Studies” and S. J. Pearce’s ““Both Sons of Spain”: Medieval Jews and Muslims in the Imagined Nation” are just three excellent recent examples.

Many of the responses to the events of this year mentioned above have emphasised the vital roles of collaboration, friendship and care in the lives of those that stand against hate and intolerance, as well as the importance of organisations and collectives that are avowedly and proudly anti-racist, feminist and queer affirmative. It is with that sentiment that I would like to close this contribution to a journal founded on and sustained by those values and practices; as we reflect on 2016 and look tentatively, but not without hope, to 2017, I extend my love and solidarity to all GRB readers and contributors, inter ali.

Leave a Reply